CIMRM 476 - Mithraeum. Santa Prisca, Rome, Italy.

See also: CIMRM 476 Mithraeum; 477 Cautes; 478 Oceanus / Saturnus; 479 Tauroctony; Paintings: 480 Upper S. wall, 481 Upper S.(contd), 482 Upper N. wall, 483 Upper, Cave , 484 Under S., 485 Under N.; 486-496 Misc. finds; 497-500 Inscriptions and coins; CIMRM Supplement - Zodiac; Intarsio of Sol.

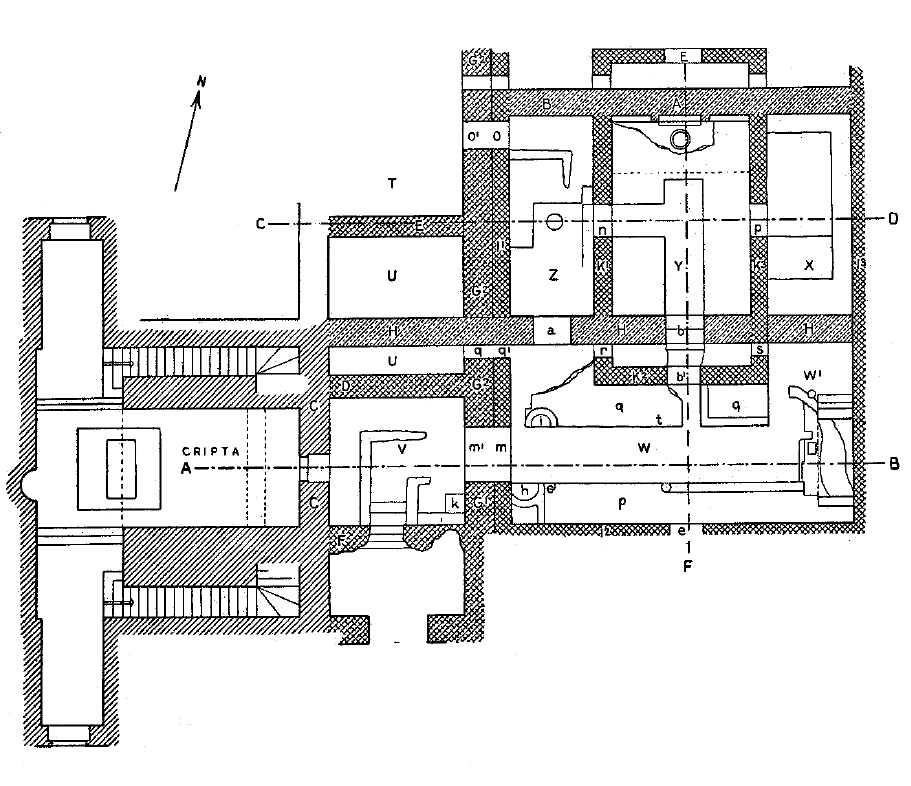

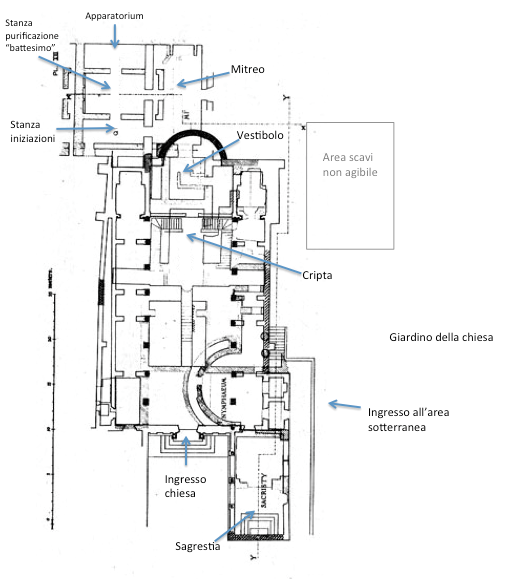

Underneath the modern church of Santa Prisca in Rome, there is a crypt (A). A modern doorway from the crypt leads east into the ante-chamber (V) of a Mithraeum (W).

The Mithraeum of Santa Prisca is important because of the remarkable frescos remaining on the walls. These, unusually, were painted with detailed text descriptions to indicate what they depict. This makes them of very great importance for understanding the cult. One side - the right-hand side, or south side - of the Mithraeum shows a procession of the seven different grades of initiate, each labelled. The other - the left hand side or north side - shows a procession of members of the Leo grade.

The Mithraeum was discovered under the church of Santa Prisca in Rome in 1934, during excavations by the Augustinian Fathers who are in charge of the church and adjacent monastery.1 It was then excavated in 1951-8 by a Dutch team led by M.J. Vermaseren.

The church stands 3m above ground-level, on the basement level of a Roman building.2 This building was originally a private dwelling house, built around 95 AD. A graffito dated to 202 AD indicates that, sometime before then, part of the basement of the house was converted into a Mithraeum, by a member of the imperial family, with the permission of the emperor Septimius Severus. At about the same time another part of the basement was taken over by a Christian group, possibly through a certain Prisca. The Mithraeum was destroyed by the Christians around AD 400.3 It was filled up with rubble and stray materials from various sources, so the list of finds is very extensive and most likely unconnected to the Mithraeum.4

The Mithraeum is entered through an ante-chamber which contains a pen, perhaps for smaller livestock. It is not large enough for a bull. In one corner of it, on the wall of the chamber, are the remains of a statue. A thigh, and fragments of a snake wrapped around the statue up to the waist, suggest that this is the remains of a statue of the lion-headed god.

The cult niche is at the east end.

The congregation of the Mithraeum was mainly Syrians, as the names of the initiates make clear; and there is also a reference to the new year on 20th November. Some of the same people were also associated with the temple of Jupiter Dolichenus on the Aventine, near the church of S. Alessio.5

1. The discovery and other remains in the area

The church of Santa Prisca claims connection with Prisca and Aquila in the New Testament. However the earliest literary evidence of a church of St. Prisca is the mention of a priest of the titulus of Santa Prisca in the synod of 499.6 Inspired by the 1920's excavations under S. Clemente, the Augustinian friars in 1935 conducted excavations under their own church. They hoped to find the original church of St. Prisca, associated with St. Peter. No such remains were found. But they discovered that the modern church stood on the walls and arches of the ground floor of a Roman house, built of brick and with barrel-vaulting. The crypt of the church was inside the house. The house itself was dated by brick stamps to around 90 AD. Exploring the house, whose rooms were choked with in-fill, they discovered a series of rooms.

The ante-chamber and Mithraeum were clearly accessible for a time in the middle ages. There were extensive skeletons and human remains, suggesting that it had been used to dispose of stray bodies. In addition there was very little marble, suggesting that this had been extracted for use in the lime-kilns.7

Despite many general claims, there seems to be no hard archaeological evidence of Christian activity in the area prior to the construction of the church of Santa Prisca some time during the 5th century.8 De Rossi claimed that paintings in an oratory in the garden were Christian and dated to the 4th century AD, but the oratory was destroyed during the building of the road and the date is not otherwise confirmed. Phillips' claim that a church existed here, contemporary with the Mithraeum, and attended by the women of the household while the men went to the Mithraeum, appears to be entirely imaginary.9

2. The first century house

The identity of the private house is uncertain. C.C. van Essen identified it as perhaps as the privata Traiani, the private home of Trajan before he became emperor.10 Coarelli dismisses this briefly and prefers Trajan's friend L. Licinius Sura, whose Baths (Thermae Surae) are known to have been situated immediately to the north and west of the site.11 Vermaseren adds that it is not at all likely be the house of C. Marius Pudens Cornelianus, mentioned in a bronze plaque dated 13 April 222 found near the church, and the basis for much speculation connected to Prisca, or Priscilla, and St. Peter.12

The was constructed around 95 AD on land cleared by Nero's fire decades earlier. It was elaborated, and later became part of the imperial estates.13

3. First phase of the Mithraeum

The first phase dates before AD 202 and consists of a single room with the usual central aisle, side benches and cult niche. This included a very fine stucco image of Mithras as the bull-killer, a reclining god (probably Caelus-Oceanus), niches for Cautes and Cautopates. It also included a cycle of frescos with numerous painted inscriptions.14

Vermaseren dates the paintings of the first phase to 190-200 AD, to the time of Commodus or slightly later, but before the Severan period, based on the type of lettering in the inscriptions.15

3.1. Dedicatory inscription

An inscription discovered in three pieces in the Mithraeum indicates that a well-connected man founded the Mithraeum following a dream.16. Height of letters 0.04.m. It reads: Deo Soli invicto Mithre/quod saepe numini eius/ex audito gratias c .... /.17 The founder was probably part of the imperial household, since the house was probably still imperial property.18

3.2. Lower-layer inscriptions

See South wall texts and North wall texts.

Little is left of the paintings of the under layer. Some idea of what they showed can be found on the lefthand (N) wall; very little is preserved on the right-hand (S) wall.

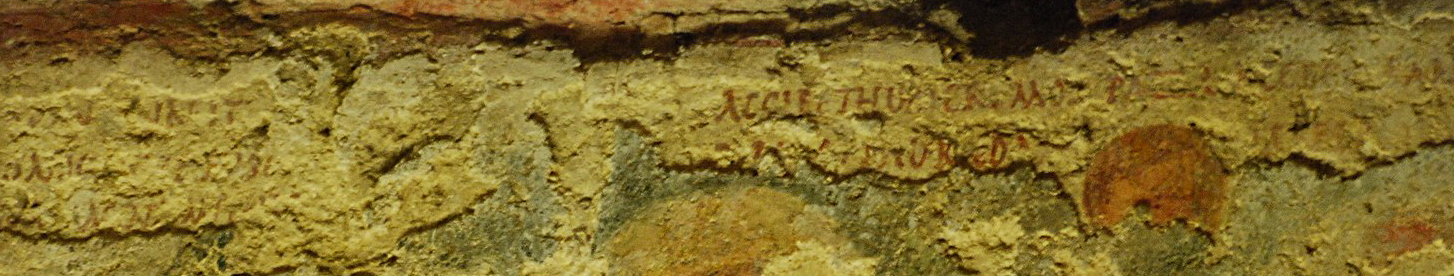

However verses appeared in columns above the paintings, and because these were at the top, many of them are preserved. They come mainly from the lower layer. All the inscriptions are damaged, but some are fairly certain.19 One of these, in col. 5 on the north wall, with reference to "you have saved us by the shedding of the eternal blood", has attracted much discussion.

3.3. The graffito

This may be found on the left-hand side of the cult-niche, and reads:

"Natus prima luce/duobus Augg(ustis) co(n)s(ulibus)/Severo et Anton(ino)/XII K(alendas) Decem(bres)/dies Saturni/luna XVIII"

I.e. "Born at dawn, the two Augusti Severus and Antoninus being consuls, 12 days before the kalends of December, Saturday, 18th of the moon." It indicates the date of initiation into the cult of someone, name unknown.

The graffito. From here.

|

The graffito explained. From here.

|

So it dates to November 20th, 202 A.D.20

4. Second phase

See CIMRM 480, right/south wall, 481, right wall contd, 482, and 483.

The temple was extensively remodelled about twenty years later. The cult room was enlarged and other rooms in the basement were taken over. The cult niche remained the focus, but the walls were repainted with new frescos. The upper-level paintings were more elaborate pictorially but the inscriptions are briefer. The hairstyles in the figures give a date of around 220 AD.21

4.1. Diagram of wall-paintings

The various photographs may be placed in context by this diagram.

5. The destruction - by "the axes of the Christians"?

From: Bryan Ward-Perkins, "The end of the temples: an archaeological problem", In: Johannes Hahn, Spätantiker Staat und religiöser Konflikt: Imperiale und lokale Verwaltung und die Gewalt gegen Heiligtümer, de Gruyter (2011), 187-197; this from p.194 (online preview):

As Richard Bayliss has recently pointed out, the archaeological evidence for Christian damage to temples is all too seldom clear-cut, and too often open to wishful thinking - as I also discovered when I tracked a number of supposed cases back to their original publications.23 Most disappointing was the evidence from the Mithraeum under the church of Santa Prisca in Rome, whose excavators believed they had found clear signs of its violent destruction by Christians, and which is cited by Sauer as a particularly good example of passionate religious iconoclasm.24 The cult-niche, with its stucco figures, was certainly badly damaged when discovered, and bits of the relief were found scattered around the room; many of the frescoes too were badly damaged. But a careful examination of the published photographs of the latter did not suggest to me that they had been savagely and systematically attacked with axes, as their excavators claimed; rather, the plaster looks to have been in a generally very poor state when uncovered, and to have decayed randomly across the wall. Even some frescoed heads, which should have been the first target of iconoclasts, were well preserved when excavated, including the haloed head of Mithras himself (which, we are told in the published report, was destroyed, not by fourth-century Christians, but by a botched attempt at restoration in 1953).25 As for the stucco figures in the niche - stucco is a fragile medium, and. while they might have been deliberately damaged, it also seems possible that they had decayed and fallen apart. The head of Mithras, although detached from its original setting, was found in very good condition - a Christian iconoclast could easily have crushed it under foot.23. BAYLISS 2004, 23-25. Bayliss discusses the thorny question of whether one can tell Christian destruction from that wrought by earthquakes, foreign invaders, or neglect. For earthquakes and temples, see ROTHAUS 2000. 39-44 and 60-61 - but see also the review (and subsequent debate) in the on-line Bryn Mawr Classical Review 2002.02.25. The case of Corinth is interesting: the excavations were good by earlier twentieth-century Mediterranean standards; but, even in this case, we cannot confidently say what brought the pagan buildings down.

24. VERMASEREN-VAN ESSEN 1965. 129-131, 151 and 241f. SAUER 2003, 134-136.

25. See VERMASEREN - Van Essen 1965, plates 53-65. The excavators too were puzzled at the survival of some of the sacred representations, though this did not deflect them from their overall interpretation: “After the destruction of the cult-niche and some of the monuments (though not others, the real meaning of which was not understood), the whole building was filled with rubbish" (VERMASEREN - Van Essen 1965, 241-242). Sauer (2003, 135-136) argues - at some length - that it was precisely because of their ‘passionate hate’ that the Christian iconoclasts wielded their axes so inaccurately! The head of Mithras, which, according to Sauer, was a particular focus of attack, is at the right-hand end of his fig. 63 (on p. 135). VERMASEREN and Van ESSEN (1965, 150) recount its true (and more banal) fate: “Of the head (of Mithras), only the outline has been preserved, with part of the halo; the rest of the face was lifted off in 1953 by the Istituto Centrale del Restauro, but did not respond to treatment and is now destroyed."

R. Bayliss, Provincial Cilicia and the Archaeology of Temple Conversion, Oxford, 2004. E. Sauer, The Archaeology of Religious Hatred in the Roman and Early Medieval World, Stroud, 2003. M.J. Vermaseren & C.C. van Essen, The Excavations in the Mithraeum at the Church of Santa Prisca in Rome, Leiden, 1965.

6. Other material

From Flickr:

In the center of the niche is the group depicting Mithras, with billowing cloak, along with the dog and the bull: there remain some fragments; the scene has been interpreted as a representation of the moment in which the god, having chased and caught the bull, drags him into the cave. At the foot is the gigantic figure of the god of another male god, lying down; either Ocean or Saturn, whose body is made up of jars covered with stucco.

Below, two other pictures illustrate moments in the life of Mithras. To the right seems to be represented the killing of the bull (a few fragments preserved); to the left, perhaps the depiction of the birth of the god from the rock. At the corners were the images of the sun, on a perforated sheet of gilded lead, and the moon almost certainly completed by the twelve signs of the zodiac.

7. CIMRM entry

The CIMRM entry is now obsolete, and is included for historical interest.

476.

In 1935 during excavations, undertaken by the Fathers Augustines, a Mithraeum was discovered in the underground rooms of a notable house, situated under and behind the absis of S. Prisca's on the Aventine. This Church lies above the house, in which an early Christian community had its meeting-place next to the house, the underground rooms of which served for the mithraists to held their services. In 1952 and 1953 I carried on the excavations together with Dr C. C. van Essen. Other seasons of work will follow, thus we are only able to publish here some preliminary details of the results. The monuments are at the moment in the Dutch Historical Institute at Rome; they will be exhibited in a small Museum in the Mithraeum itself. We thank the Sopraintendente Prof. Dr Pietro Romanelli and Dottessa Bianca Maria Felletti-Maj for their warm interest and effective help. An extensive description of the different succeeding periods of the Roman house, of the Mithraeum and of the new finds will be given in a separate book.

A. Ferrua, "Il Mitreo di S. Prisca", in La Civiltà Cattolica, 17, 2, 1940, 298ff; A. Ferrua, "Il Mitreo sotto la Chiesa di S. Prisca", BCR22 LXVIII, 1940, 59ff. Reprinted in Monumenti di Roma, 3, Roma 1941.; Lugli, Mon. Ant. Suppl.23, 56ff; Fuhrmann in Archaeologischer Anzeiger 1940, 478f; Merlin in Revue archéologique (S.6) XVII, 1941, 40ff; Leopold in de Nieuwe Rott. Cour., 8 Aug. 194224; Cumont in CRAI25 1946, 401 ff; Vermaseren, Mithrasdienst, 55f. See figs. 129 and 130.

By a modern entrance one enters a long, spacious passage and descends by several steps into the vestibulum of the spelaeum. The Mithraeum was built towards the end of the second century A.D. in the underground rooms of a house, which was constructed itself in the time of Hadrian. Towards the end of the fourth century it was destroyed by the Christians and filled up with rubbish. The entrance-hall has been built in a rather extraordinary way, for within a small and rough, enclosing wall (H. 1.15) with only a very small entrance, a red painted altar(k) has been erected (H. 1.15 Br. 0.57 D. 0.68), in front of which there is only a little room.

On the South wall (F2) there are two snake-like figures, which seem to be the legs of a Gigant (cf. No. 491). Against the same wall a very narrow bench was constructed. This enclosed part of the entrance-room may have been used for preserving and killing of small cattle. Two other benches were constructed against the walls C and D.

By m one enters the actual sanctuary (L. 11.25 Br. 3.50), which consists of a paved central aisle (Br. 1.60) and two sloping benches (H. 1.00 Br. 1.35), on which traces of red painting are visible. Bench p was originally interrupted by entrance e, but later on it was extended all along the wall. In its front near g, in a bluishly plastered. hollow, a deep, paunchy jug (largest diam. 0.60) had been dug in. The other bench q is much shorter and is still interrupted by a small passage, which leads to b, where by steps one can enter the side-room Y (originally the central room of the house). Near t a narrow, oblong shaft was walled into the bench. The two benches have along the front a projecting ledge, covered with marble, and they support near their beginnings the semicircular, plastered niches h and i (H. 1.75). Niche h (diam. 0.90), painted in an orange colour is connected with the South wall by a small wall, on which a trapezium in red, green and white (different periods of painting). The niche contains a statue of Cautes(see below No. 477). The dark purple niche i (diam. 0.66 however,) is not connected with the wall behind it and stands clear. A statue of Cautopates, which must have been standing in it, was not found back.

As said above, bench p, which can be ascended via one step c and via two other steps, runs on as far as the high, plastered cult-niche, whereas q stops at some distance (2.75) from it already. A single small wall (H. 1.22) forms the substructure of this niche, which consists of an arched vault, supported by two columns, which are decorated with acanthus-leaves. The use of tuff gave the whole the appearance of a cave (H. 2.35 Br. 2.36 D. 1.20), which was decorated by polychrome stucco in different periods.

Best preserved is a figure of Oceanus-Saturnus, who lies stretched out over the entire breath of the niche (see below). With his l.h. he holds an amphora, out of which a fountain spouts up. The water falls in a plastered vessel (H. 0.55 Br. 0.52) and flows again away from it through a lead pipe into a basin in the pavement of the central aisle.

On the sides of the niche scenes of the bull-killing in stucco and of Mithras' birth (see below).

In two succeeding periods the side-walls of the Mithraeum were painted abundantly (see below) and provided with many dipinti.

On the right side of the Mithraeum there must be different rooms accessible by entrance e, which are not yet explored. On the left side, however, there are three adjacent rooms. One enters by a room Z (L.6.90 Br. 2.80), in which against wall I1, a bench had been constructed. Along wall K1, is a very narrow corridor leading to entrance n. At some distance of this door a second bench had been constructed, which joins with the first one. Behind it there is (beginning at o) a rough wall. Both benches are plastered and have traces. of red colour. In the podium-like floor a jar was found (see below).

Room Y (L. 6.90 Br. 4.55) shows after the last excavations a central aisle and two low side benches and has generally the same appearance as the Mithraeum itself. The l. bench originally was interrupted by a narrow corridor at entrance n; the r. bench however, continued along the side-wall K3 and next to entrance p it contains a vessel.

The central aisle leads to a much higher podium, which was constructed before a niche built against the wall A (the surface of the plastered niche shows many traces of blue; it has to be restored). In the podium itself there was a second vase. Room X is only accessible by room Y. It has two benches.

Many figures reproduced are given by the Institute for Christian Archaeology in Rome We feel obliged to thank Mgr Giulio Belvederi for this important material.

8. Bibliography

- G.B. De Rossi, "Dell'oratorio antico scoperto nello scorso secolo presso S. Prisca", in Bullettino di Archeologia Cristiana, serie 1a, 5 (1867), pp. 44- 48. Online here. Via online bibliography here.

- A. Ferrua, "Il Mitreo di S. Prisca", in La Civilta Cattolica, 17, 2, 1940, 298ff. Brief popular article.

- A. Ferrua, "Il Mitreo sotto la Chiesa di S. Prisca", BCR LXVIII, 1940, 59ff. Reprinted in Monumenti di Roma, 3, Roma 1941. (Bullettino della Commissione archeologica Communale di Roma (et. BCM). From 1939: Bullettino della Commissione archeologica del Governatorato di Roma.) (CUL shelfmark NF4 P520.b.31). Full publication.

- A. Ferrua, "Recenti Ritrovamenti a S. Prisca", RAC 17, 1940, 271ff. (Reference in CIMRM 1, p.14)

- G. Sangiorgi, S. Prisca e il suo mitreo, Roma, 1968

- U. Bianchi, Mysteriae Mithrae. Contains colour plates of the frescos and monochrome images of some of the texts.

- M. J. Vermaseren; C. C. Van Essen, The Excavations in the Mithraeum of the Church of Santa Prisca on the Aventine, Leiden: Brill, 1965. - Excavation report. Reviewed in Journal of Biblical Literature 85 (1966) 115-116+118, by Kyle Meredith Phillips, Jr. JSTOR.

- M.J. Vermaseren, "Nuove indagini nell'area della basilica di S. Prisca in Roma", in Mededelingen van het Nederlands Instituut te Rome. Antiquity, n.s., 37, 2 (1975), pp. 87-96. Via online bibliography here.

- Coarelli, F. 1979, Topografia mitraica di Roma, in Mysteria Mithrae. Atti del seminario internazionale su "La specificità storico-religiosa dei misteri di Mithra, con particolare riferi - mento alle fonti documentarie di Roma e Ostia", Roma e Ostia 28 - 31 marzo 1978, Rome, 69-79.

- R. Krautheimer, Corpus Basilicarum Christianarum Romae. Le basiliche cristiane antiche di Roma (saec. IV-IX), vols. I-V, Vatican City, 1937-1980: vol.III, 263-279. A very useful description of the church in English in a volume too large to photocopy without difficulty.

- Margherita Cecchelli, "Dati da scavi recenti di monumenti cristiani. Sintesi relativa a diverse indagini in corso", Mélanges de l'Ecole francaise de Rome 111, 1999. p. 227-251. Review of recent archaeology. Online at Persee.fr but some illustrations omitted.

- G. Lepore, "Santa Prisca", in: Materiali e tecniche dell'edilizia paleocristiana a Roma, ed. M. Ceccelli, Roma 2001, pp. 339-342. According to Cecchelli this has interesting discussion of some of the early Christian brick structures.

- M. Cecchelli, "Scavi e scoperte di archeologia cristiana a Roma dal 1983 al 1993, in Atti del VII Congresso Nazionale di Archeologia Cristiana. I, Cassino 20-24 settembre 1993", Cassino, 2003, p.335-356. From Spera, "Characteristics".

- M.G. Zanotti, in: LTUR ( = Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae) IV, 1993‑2000, p.162-163. From Spera, "Characteristics".

| 1 | A. Ferrura, S.J., "Il mitreo di Santa Prisca, (Monumenti di Roma, 3)", Bollettino della Commissione Archeologica Comunale 58, 1948 [1941] p. 59 ff. The article is described as "excellent" by Vermaseren, p.ix. |

| 2 | Krautheimer, l.c., who also states that remains of the ground-floor level of the building stand as high as 9m, incorporated into the east walls of the church. |

| 3 | Phillips, l.c.. |

| 4 | Vermaseren-Essen, p.338 f.: "The rooms of the S. Prisca Mithraeum were filled with rubbish about A.D. 400 and the excavations produced thousands of fragments of all sorts of minor objects. Although it has not been possible to provide a detailed and specialized catalogue it has seemed better to publish a limited description of this material. thus making it available to students, rather than to ignore it altogether." |

| 5 | Vermaseren, "Nuovo..", p.92: "Questo santuario è - come provano i nomi dei fedeli ed anche l'allusione alla festa del nuovo anno al 20 Novembre - soprattutto frequentato dai membri siriaci. Poi questi Mithriasti siriaci presso Santa Prisca avevano connessioni col santuario di Giove Dolicheno sullo stesso Aventino presso S. Alessio." (This sanctuary - as evidenced by the names of the faithful and also the allusion to the New Year's holiday 20 November - was mainly attended by members of the Syrian community. These Syrian Mithriasts at Santa Prisca also had connections with the shrine of Jupiter Dolichenus on the same Aventine, at S. Alessio.) |

| 6 | Lucrezia Spera, "Characteristics of the Christianisation of Space in Late Antique Rome: New Considerations a Generation after Charles Pietri's Roma Christiana", in: Cities and Gods: religious space in transition, ed. Ted Kaizer &c., Peeters, 2013, p.121-142 (online here: "If the chronological limits of the first parochial institution are fixed at the period of the pontificates of Celestine I and Sixtus III (AD 422-440), the earliest mention of the church of Prisca on a site that was probably different from that of the 12th-century building, is given by the synod of 499. (80)" Note 80: "MGH, Auctores antiquissimi XII, 413. See van Essen 1957; Sangiorgi 1968; Krautheimer 1937-80, III, 263-279; Cecchelli 2003, 345-356; a synthesis is offered by M.G. Zanotti, in LTUR IV, 162-163." |

| 7 | A. Ferrua, l.c., BSR 68, 1941, p.96: "Nel tardo medio evo venne ancora visitato da quei cercatori di materiali, che in tempi di miseria riutilizzavano nelle loro costruzioni quanto venisse loro alle mani. Cosi a quella parte di muri che ancora restava al disopra delle terre di riempimento venne sistematicamente strappato il paramento interno di laterizio, specialmente all'ingresso, nel vestibolo e nell'arcone dell'ambiente Y. E se tanta povertà di marmo ci è pervenuta si deve forse attribuire alle sonde che costoro fecero qua e là nel terreno... Forse fu questa una misura per sterminare piu compiutamente il ricordo di un culto esecrato? lo non lo saprei affermare. Tale ad ogni modo fu l'effetto, e fino in tempi assai recenti l'antico delubro di Mitra non si riaprì ogni tanto che per accogliere cadaveri abbandonati, come talvolta usarono gli antichi cristiani per rendere piu inespiabile la profanazione degli aborriti santuari(31)." Note 31 reads "Un vero cimitero di ossa e scheletri anche interi fu ritrovato negli strati superiori delle terre, che occupavano vestibolo e mitreo, sino alla volta." ("In the late Middle Ages it was still visited by those seekers of materials, who in times of misery broke up and refused them in their buildings. Part of the wall that still remained above the land fill was systematically stripped of its internal facing of brick, particularly the entrance, the vestibule and the environment near arch Y. And if there is so little marble found, we should perhaps attribute this to the probes that they made here and there in the soil ... Maybe this was a measure to more completely exterminate the memory of a much-maligned cult? I do not know. This however was the effect, and what was until very recently the ancient sanctum of Mithras was opened to accommodate abandoned corpses, sometimes used by the early Christians to desecrate irreversibly the detested shrines(31)"... "A veritable graveyard of bones and even complete skeletons was found in the upper layers of earth, occupying the vestibule and Mithraeum up to a certain period.") |

| 8 | Phillips states that Vermaseren and Essen do state the creation of a church ca. 220: "At about the same time the Christians, perhaps through a certain Prisca, were permitted to take over another part of the basement for what was to be the titulus of Santa Prisca (pp. 114-15)." TODO: Look at this. Note that Vermaseren is often insufficiently critical when it comes to Christianity and Mithras, and fails to ask whether the data actually justifies the claims. This is also seen when discussing the destruction of the Mithraeum which he attributes to "the Christians" without actually sifting the data and establishing the date of the events. |

| 9 | Kyle Meredith Phillips, Jr., Review of Vermaseren-Essen, Journal of Biblical Literature 85 (1966) 115-116+118. Online at JSTOR: "Why, as stated by the authors, is the same physical proximity between Christians and devotees of Mithras found under San Clemente and at least once in Ostia? How or why did they live side by side rather peacefully for nearly 150 years? Are the similarities between the two cults in the early third century strong enough to postulate that the masculine worshipers of Mithras someway encouraged the female members of their families to attend the neighboring Christian mysteries? These questions might be partially answered if further excavations could be carried out under Santa Prisca." It perhaps reflects more the cultural assumptions of an American man in the 1960's about churchgoing being "womens' stuff" rather than anything else. |

| 10 | Vermaseren, "Nuovo...": "Il C. C. van Essen ha cercato di provare che si sono diverse ragioni per ritenere che il Palazzo traianeo sia da identificare con le Privata Traiani. Benché probabile, questa ipotesi non è sicura." (C.C. van Essen has sought to prove by various arguments that this Trajan-era palace should be identified with the Privata Traiani. This is very likely, but it is not certain.) |

| 11 | F. Coarelli, "Topografia Mitriaca di Roma", in: Mysteria Mithrae, ed. U. Bianchi, (1979), p.69-83; p.75: "Uno dei più importanti mitrei di Roma, scoperto nel 1935 entro i resti di una grande casa dell'inizio del II secolo d.C., situato sotto e dietro l'abside della chiesa. La proposta degli editori (M.J. Vermaseren, C.C. van Essen, The Excavations in the Mithraeum of the Church of Santa Prisca in Rome, Leiden 1965) di identificare in questo edificio i privata Traiani sembra improbabile. Più verosimile semmai il collegamento con L. Licinius Sura, la cui domus sorgeva negli immediati paraggi delle Terme Surane, localizzabili con certezza nei pressi di S. Prisca, a nord della chiesa." |

| 12 | Vermaseren, "Nuovo...": "Dobbiamo dire subito che per altre circostanze, non è nemmeno probabile che questa casa sia appartenuta al C. Marius Pudens Cornelianus del quale vicino alla Chiesa fu trovato il diploma in bronzo offerto a lui il 13 aprile 222 dal concilium conventus Clunieni. Non si tratta di negare connessioni eventuali di questa illustre famiglia con Prisca, ovvero Priscilla, ma di prevenire conclusioni non conformi a criteri scientifici." |

| 13 | Phillips, l.c.. |

| 14 | Phillips, l.c.. |

| 15 | Vermaseren-Essen, p.177: "The data for the lower layer are much scantier. It is, of course, earlier than the upper layer but not much. On the one hand, what little is visible of the colours shows a refined sense of gradation, which is already Severan in flavour. The type of letter in the inscription, on the other hand, is heavier and shorter than that of the upper layer, but not square as the true Antonine type, nor perpendicular as that of the time of Septimius Severus (c. A.D. 205) in the Terme dei sette sapienti, Ostia III, x. This gives a date of the time of Commodus, or somewhat later, in the decade A.D. 190-200." |

| 16 | Vermaseren-Essen, Catalogue W17, p.340-1: "White marble slab (Ht. 0.24. W. 0.63. Thickness 0.02) broken in three fragments (PI. LXXV. 5).... Since two of the three fragments were found in the neighbourhood of the niche. it is not impossible-although by no meRns certain- that the inscription belonged to the niche. It is indeed unfortunate that the provenance of the second fragment has been so badly indicated that one cannot confirm this conjecture. However, the inscription fits on one of the steps in front of the niche..." |

| 17 | Vermaseren-Essen, p.340: "numini eius. cf. CIL VI. 724 (Rome) mentioning numini invicto Soli Mithrae, in which the word numen is an equivalent for deo. ... In this inscription the word numen followed by the genitive dei means the power of the god. There are many examples of this use in epigraphical texts.. Ferrua. p. 6 supplies : gratias et vola reddere moniti sunt, which is quite correct. In Greek and Roman religion the divinity himself sometimes summons the pious devotee by means of a dream or in some other way to give a votive offering or even to build or to restore a temple." |

| 18 | Vermaseren-Essen, p.117: "During the reign of Septimius Severus who, probably under the influence of his Syrian wife, favoured the Oriental cults, an important Roman Mithraist whose name is unknown gave permission for a sanctuary for the Persian god to be built in his house, having been enjoined to do so by the god himself (Cat. W 17). He probably belonged to the Imperial family, since the house in which he lived had been built more than a century earlier by the Emperor Trajan (see p. 107) and had remained Imperial. He certainly became the Pater, the head of the new community." |

| 19 | Except where indicated, all this information is taken from Vermaseren-Essen, chapter 21, p.187-240. |

| 20 | Vermaseren-Essen, p.118: "The graffito has the form of a horoscope, though without mentioning the zodiacal symbols, and it is striking that the writer does not menton his name. There is a parallel for this in a genuine horoscope at Dura Europos, written on a wall of the workroom of a businessman in the "House of the Archives". ... it is clearly indicated that it was inscribed during the consulate of the two Augusti, Severus and Caracalla, i.e. in A.D. 202... The writer of the graffito on the cult-niche was natus on November 20th, A.D. 202, at the first light On the dies Saturni." |

| 21 | Vermaseren-Essen, p.173-177. E.g., p.173: "The material for this is derived entirely from the western half of the south wall ... since the remainder of the figures are either too indistinct (western half of the north wall), or are shown with ritual attire and coiffure. ... The man leading the ram has, however. a great part of his cheeks clean shaven and probably has only the short side-whiskers just in front of the ears (sec left cheek) which is typical of the side-whiskers of the reign of Elagabalus (A.D. 218-222). If he wears a short pointed beard, which is possible but not certain, it may also suggest the first years of Severus Alexander." |

| 22 | BCR = Bullettino della Commissione archeologica Communale di Roma (et. BCM). From 1939: Bullettino della Commissione archeologica del Governatorato di Roma. |

| 23 | "Mon. Ant." = Monumenti antichi pubblicati per cura della R. Accademia nazionale dei Lincei. |

| 24 | = Leopold, H. Uit de Leerschool van de Spade CDXXXIX, Iets nieuws omtrent het Mithraisme. Nieuwe Rotterdamse courant, 8 Aug. 1942. |

| 25 | = Comptes Rendus de l'academie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. |

| Tweet |